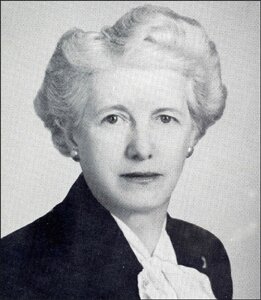

Our personal communication was limited to about one precious hour many years ago at a national convention. I had read most of her books and was thrilled that she would invite me to slip away to a secluded corner, protected from the many people who wished to speak with her. We talked about the past and what it has to offer the future. Like countless others with whom she shared her insights, I believe her wisdom should not be forgotten. The following conversation is created from her written works. For physical educators young and old, she remains a voice of reason that should be heard.

What was physical education like when you were a little girl in Centerville?

Structured and rational physical education, as was practiced in Iowa’s German communities like Davenport, did not exist in Centerville during the 1890s. We had no organized calisthenics, gymnastics, sports, rhythmical exercise or dance. A tri-county conference was held in Centerville in November 1898 that included a program concerning how physical development could be encouraged.

A Professor Stomp, in discussing the topic, criticized the lady teachers present for their own neglect of physical exercises, saying some women teachers were so physically inefficient, they could not perform their teaching duties properly. This is my earliest memory of anyone in Centerville suggesting that physical development could improve learning.

In fourth grade I drew for my wonderful teacher, a Mr. Bower. He was a Civil War veteran. When the school bell rang announcing that the morning or afternoon session was to open, we children lined up before the big entrance door in two’s according to our room assignment and within that group according to the location of our seats. Then on signal, we marched up the stairs and down the hallways into our own room, and then up and down the aisles in a given order until we reached our assigned seats, all the time singing whatever song our song monitor started for us and standing at attention at the side of our seat until we had finished the song. Then we were seated in unison.

We sang The Union Forever--Hurrah Boys Hurrah, Marching Through Georgia, and Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, The Boys are Marching. Mr. Bower let us sing at the top of our lungs, and taught us to swing our arms as we marched, thus getting some excellent chest and shoulder development exercise. Later educators called this type of activity “regimentation’ and deplored it. But we loved it!

That marching and singing in unison gave us a sense of togetherness and an uplift that we never would have acquired from entering the schoolhouse informally and independently. Throughout my whole life I have remembered the joys of marching and singing together. After fourth grade, I transferred to the Central Ward School that was a 4.5-mile round-trip walk I enjoyed daily with my friends in rain or shine, snow and wind. We sometimes marched and sang all the way.

How did you recover so well from your many serious childhood illnesses?

As I was growing up, Mother was becoming aware of the havoc wrought in me by earlier years of so much illness and frailty. I was hollow chested, round shouldered and underweight. It was quite understandable that Mother was the easy victim of a ready-talking salesman who sold her a set of shoulder straps, which I was to wear throughout the school day.

As long as I kept my shoulders back, all was well, but the minute I relaxed, little metal pin-like fingers bit into my flesh to remind me to straighten up. I deplored my poor posture and wanted badly to improve it, so I wore the contraption until my upper back became very sore from the many prickings of the relentless metal fingers. Mother and I eventually discarded the straps, and we continued hoping to find a better way to reform my deformed body.

Even after I transferred to the Central Ward School, Mother was still worried about my round shoulders, hollow chest, and generally deficient posture. She talked to our family physician and neighbor, Dr. Sawyers, who happened to have a daughter with whom I went to school. She also had postural deformities, and Dr. Sawyers was seeking ways to help her find a cure. While visiting the East Coast, he learned of numerous physical training innovations and techniques he could use.

Dr. Sawyers purchased and installed some of the equipment in a large room in this home. His daughter and I went there several times a week after school to train. We had stall bars, flying rings, wall pulley-weights, a rowing machine and a few other pieces. How fortunate I was to use these marvelous devices, and what a tremendous impact they had on my early development. I was eleven or twelve years old at the time. We did not know of anyone in town who could teach us how to use the equipment, so we experimented on our own. The stall bars were particularly puzzling. I was surprised later in life when I went to college and was educated in their use, that there were so many exercises we could have done on them had we been properly instructed.

Did physical education evolve much in the Central Ward School while you were a student there?

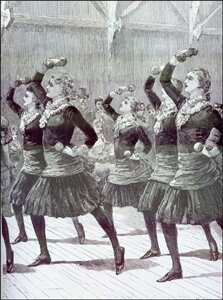

The great wide hallway on the first floor of the Central Ward School was lined with racks filled with dumbbells and Indian clubs. I had never seen or heard of such things before, and I could scarcely wait for the day when our room might have a chance to use these strange things. A new teacher had persuaded the superintendent and the school board to invest in them and to give all the children a turn at them. One day we were marched to the hallway where we were given dumbbells and taught a drill to do with them. It was an exciting moment for me.

Later we were given the Indian clubs, and those who worked hard were allowed to put on a drill at the eighth grade commencement exercises in May 1897 at the Opera House, a building on Drake Avenue that doubled as a military armory. I was one chosen to be in that memorable drill. Although I could never be persuaded before that to take part in even a Sunday school program, this bit of public appearance I gladly entered upon and enjoyed doing as part a large group offering.

Those calisthenics using dumbbells and Indian clubs were marvelous exercises, and I wondered why we hadn’t been allowed to drill with them all year long. For four years I saw them hanging in the racks on the first floor hallway but they were never used until some group had to learn a drill for a program that our families, friends and the townspeople would attend.

I wished we might use them all the time whether anyone was going to see us or not, but apparently they were looked upon by the school authorities merely as equipment for “show-off,” and no teacher was assigned to make use of them as part of an educational program. Before my eighth grade year ended, I was allowed to swing those clubs once more. It didn’t concern me one bit that I was just swinging them to be swinging them and not to be in a show. It was the doing of it that I loved, not the public performance.

Dumbbells and Indian clubs would be all but forgotten by the mid-1920s. I recall a group of twenty-four boys from the German Turner system doing a dumbbell drill demonstration at the Central District Convention held in Chicago in 1923, and that was about the end of those wonderful activities. Like the marching, singing, stall bars, and traveling rings I so much enjoyed as a child, club swinging and dumbbell drills became only a wonderful memory.

You pioneered the game of basketball in Iowa. How did you discover it?

By the mid-1890s, basketball had spread from its 1891 birth in Springfield, Massachusetts, to the farther reaches of the country. Not a breath of it, however, had permeated into the smaller towns of Iowa.

The game was completely unknown to us until our neighbor, Edna Stanton, attending a girl’s school, Ferry Hall, in Chicago, came home for Christmas vacation of 1898 and told us of the new game of “basketball’ being played at her school—a game which called for the players to wear bloomers. I was as exited about wearing bloomers as the new game. I pestered Edna to promise when she came home for the summer to bring me more news about it—a promise not kept, however, since she did not care for the game and apparently gave it no further thought.

We moved north to Spencer, Iowa in the summer of 1900, and I began high school there. I was still obsessed with basketball but had no luck convincing others to play it during my freshman year. We moved back to Centerville the next year, and Father convinced the members of the school board, the superintendent of schools and the high school principal on my behalf to give basketball a chance in Centerville. The first game of basketball ever played in Centerville, Iowa, was on May 2, 1902. The court was the lawn on the north edge of town where few would see us; our uniform, chemise and petticoats, were rolled at the waist to shorten them.

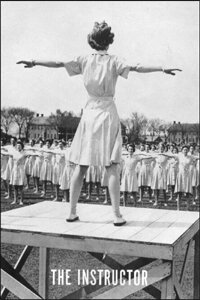

These few questions cannot begin to cover your rich and productive life. Your days at Coe College could fill a book. You studied at the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics during the Golden Era of physical training, and you were a giant in the field of physical education. You championed the teaching of rational body mechanics and conditioning for both genders, and you were a guiding force for the innovative women’s military physical training doctrine during World War II. It is amazing that you and the others that stayed grounded in physical training during the 1920s and 1930s were able to rebuild performance-based functional physical education with so little resources and in so short a time.

Physical education drifted away from fundamental and rational physical fitness toward an overemphasis on sports and games with the “New Physical Education” following the “Battle of the Systems” in the 1920s. World War II was an abrupt and sobering awakening.

Women were called upon to do physically demanding work, and that whole period reminded many of us that body mechanics and conditioning exercises are the keystones of the physical education program. I was fortunate that in my youth, I was forced to correct my own poor posture and unnatural body management habits. I was also trained under the watchful eye of Amy Morris Homans and her faculty at the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics.

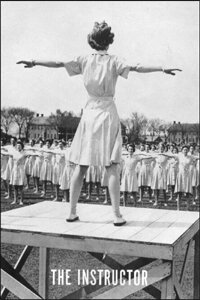

WAC physical training in barracks My background prepared me for those times, and we who worked to make our women physically fit during that war emerged on the other side appreciative of all the teachers who readied us for the immense challenges we faced.

In the 1930s, Margaret Culkin Banning reported that of the thirty-seven million adult women in the United States, only three million were employed. Five million of the unemployed were past sixty, leaving nineteen million who were  either homemakers or merely idle. World War II dramatically changed those figures. The War motivated many millions of these women to work, and it became clear that they would need to be more fit to do the jobs that needed to

either homemakers or merely idle. World War II dramatically changed those figures. The War motivated many millions of these women to work, and it became clear that they would need to be more fit to do the jobs that needed to  be done while the men were in uniform. For the newly formed Women’s Army Corp, it quickly became apparent that they too lacked the strength, flexibility and endurance the times would require. We all worked hard during those years to reform ourselves. That’s a whole other story.

be done while the men were in uniform. For the newly formed Women’s Army Corp, it quickly became apparent that they too lacked the strength, flexibility and endurance the times would require. We all worked hard during those years to reform ourselves. That’s a whole other story.

Your entire life is an important story that should be told to every young physical educator.

Maybe so.

Ed Thomas is the Iowa Department of Education Health, Physical Education, and Substance Abuse Prevention Consultant.

Recommended readings:

Lee, M. (1937). The conduct of physical education. New York: Barnes and Noble.

Lee, M. & Wagner, M. (1949). Fundamentals of body mechanics & conditioning. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

Lee, M. (1963). The history of the Middle West Society of Physical Education. Nebraska: Central and Midwest Districts Associations of Health, Physical Education and Recreation.

Lee, M. (1977). Memories of bloomer girl. Washington, D.C.: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation.

Lee, M. (1978). Memories beyond bloomers. Washington, D.C.: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation.

Lee, M. (1983). A history of physical education and sports in the USA. New York: Wiley.

either homemakers or merely idle. World War II dramatically changed those figures. The War motivated many millions of these women to work, and it became clear that they would need to be more fit to do the jobs that needed to

either homemakers or merely idle. World War II dramatically changed those figures. The War motivated many millions of these women to work, and it became clear that they would need to be more fit to do the jobs that needed to  be done while the men were in uniform. For the newly formed Women’s Army Corp, it quickly became apparent that they too lacked the strength, flexibility and endurance the times would require. We all worked hard during those years to reform ourselves. That’s a whole other story.

be done while the men were in uniform. For the newly formed Women’s Army Corp, it quickly became apparent that they too lacked the strength, flexibility and endurance the times would require. We all worked hard during those years to reform ourselves. That’s a whole other story.